Offerings from Listening to Ghosts

A Rippled Reflection on Communal and Environmental Arts Practice

Joshua Ralph (they/he) is a community-engaged eco-artist. Their environmental outreach projects have been recognized in publications including The National Observer, and their art reflects a commitment to both ecological healing and creative transformation.

Raised on Treaty 2 Territory and now living as an uninvited settler on the lands of the Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations, Joshua brings a deep awareness of place, change, and responsibility to their work.

In this deeply thoughtful and intentional personal essay, Joshua reflects on The Freshwater Monitoring Art Kit. This project allowed participants to take part in freshwater testing around the lakes and streams of Metro Vancouver in 2024.

With histories laid under meters of gravel and concrete, what remains of the freshwater systems between fragmented forests?

If the water could speak, what might it say?

Are we willing to listen?

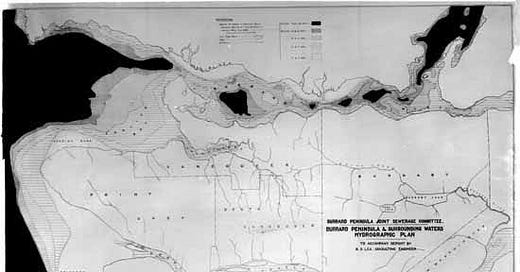

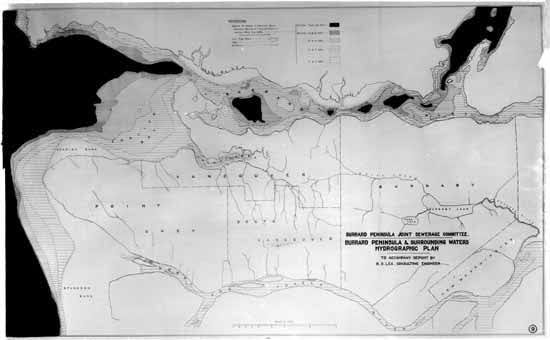

Upon arrival in so-called North America, settler goals determined that low-lying fertile valleys, especially those offering temperate climate and ample freshwater supplies, provided an excellent domain for urban sprawl. In a less-than-ideal coincidence, these same ecosystems proved to be critical habitat for resident fish. Records indicate that upwards of fifty streams once emptied their waters into the Burrard Inlet, Fraser River, and English Bay.

Presently, these streams, which connect land to ocean, are considered lost, having since been converted to sewers or backfilled1 to produce parking lots for major grocery chain conglomerates. Petroleum pavement, the distilled and chemically processed corpses of those that lived eons ago, trace borders between bodies and flood neighbourhoods, “reminding us of the life that once teemed here when the place… was home to myriad species who made life, made worlds.”2

As the region of the Lower Mainland continued its colonial operations throughout 2021, mass forest fires ravaged the interior forests of the province, burning some 870,000 hectares of wilderness3. City residents, safeguarded from the threat of fire by shoehorns of steel and concrete, breathed toxic smoke plumes over the span of months. On an international level, an increasingly dire IPCC report was released, presenting a near-impossible horizon for meaningful climate action. It was the year I began to explore material processes and ethical environmental engagements.

~~~

I stroll the wooden staircase down to Still Creek, one of the last remaining partially-open stream systems within the municipality of Vancouver, left for over a century “untouched more out of neglect than conservation.”4 I’m met by the liquid melody of an American Robin, a city resident chortling her locale from forty feet above the frosted forest floor. A few seconds later, rahhhh rahhhh, a Steller’s Jay belts out a morning alarm for their canopy colleagues, seeking out breakfast within the crouched January breeze. Another joins suit, charting lines through thinned skies towards the bus loop connecting much of the human communities of East Vancouver to adjacent neighborhoods.

Surrounded by second-growth Hemlock and Sitka Spruce, I breathe in the scent of nearby Douglas-fir, taking notice of the thick bark that separates their delicate innards from the newly-frosted elements. Decades worth of stored sunlight to grow taller, transporting water and nutrients to their crown.

Because of the region’s historically long and comparatively dry summers, conifers predominate the expanse of the Lower Mainland. Douglas-firs are the most encountered species, closely followed by Cedars and Western Hemlock, in union with their deciduous relatives, Red Alder, Black Cottonwood and Bigleaf Maple, each contributing their piece to the cooperative alliances between species lines, co-creating the “vital systems of reciprocity: water, light, and soil minerals.”5

A closer look atop the bark reveals lichen sprawling the circumference of the premature trunks. An algae wrapped in a fungus, these living fossil plants trace their lineages back as direct links to the Earth’s original oceanographic photosynthesizes. A collaborative dance across species lines that began life in the primordial seas, filling oxygenated air with roots deeply spread in the waters of bygone eras, creating the environs of all living beings.

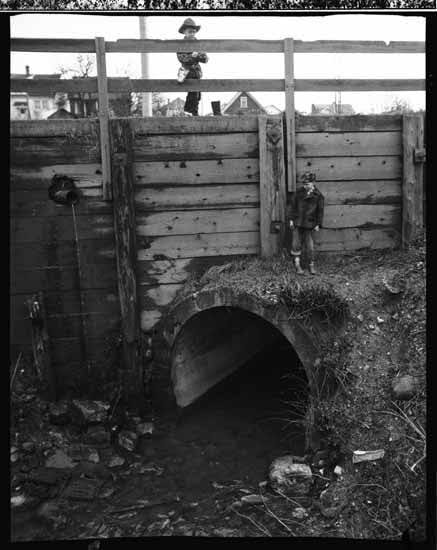

I kneel before the streambed, some ten feet of distance occupying the space between myself and the other side of the slow current. The shallow water will flow onwards towards Burnaby Lake, but not before disappearing below culverts and the underbellies of roadways, finding its final destination in the Pacific. Known locally once as one of the most polluted waterways within the city6, the stream had welcomed its first breeding salmon return in nearly a century years just 13 years ago7, with the small forest cover serving as a refuge for the fragmented populations of species that call this place home. A space of coalescence for some, a sever between the land of blocks and crosswalks for others.

I exercise the moment of calm to trial an idea: I dip the digital thermometer into the cool water, noting the screen’s reflected temperature, proceeding to measure pH, alkalinity, chlorine, dissolved oxygen, and conductivity of the stream. Cupping the flowing water below my feet, I fill a shallow dish, adding drops of coloured inks to the sample, with each choice corresponding to the specifics of the data observed moments prior. A sheet of paper is dunked and swiftly lifted from the inky water surface, revealing an explosion of hues and textures, stamped with coordinates, and set aside to dry in the frosted air. Images sealed to the page, the paper visually realizes the data hidden within the stream’s flow, withdrawing inked reflections of still-flowing ghosts of the prior-to-city past.

“There are fossils of seashells in the Himalayas; what was and what is are different things”

— Rebecca Solnit8

The stories of these historical ecosystems, of rivers and creeks stripped of sunlight for nearly a century, led to a journey of uncovering. These stories revealed truths of this colonized landscape and of extractive relationships, both of bygone decades and cycles of ongoing exploitation.

With eagerness, the project secured funding streams for its continuation, culminating into the Freshwater Monitoring Art Kit. As a collaborative program, it welcomed volunteers to the shores of these freshwater systems. A narrow range of parameters in these water’s flows determines the subsistence and continued lineage of beings across intertwined ecological processes, from fish to sedges to cedars. Participants followed suit to the lull of the water’s rush, communally producing the same generative artworks tested on the shores of Still Creek. The Art Kit offered palpable images of change. Artworks were created based on compiled data on the site’s chemical components following each site visit, with an imagined view collectively coming to light of what once thrived in contrast to what and with whom these spaces are shared within the present.

Mary Oliver (Unmarked) wrote that, “Attention is the beginning of devotion.”9 In reply, artist, Kristian Brevik (Settler) asks, “what is the end?”10 The project evidenced in itself that loss became noticing, became displacement; did we listen to the water, or did we extract?

Dominant scientific discourse11 relating to ecology was developed in the early 19th century. Stemming from biology, ecology studies how organisms relate to each other within their shared surroundings. Under a holistic interpretation, ecology seeks to examine interactions between this understanding of living and non-living beings within the broader context of place. For those raised within colonial knowledge systems, scientific study can be known by its trial and error, measurement and experimentation, of extracting data and of relay. Though empirical methods are not unique to dominant science, the subsequent accepted modes of disseminating resulting information are of charts and equations and management plans. This same reporting system is largely represented in climate change discourse and communication, in the stories that are predominantly echoed of changed landscapes, and of the people affected.

This space swells with resounding urgency: pristine nature on the imminent verge of destruction, the last percent of a species remaining, record-high sea levels threatening livelihoods. Though in no particular reference to past or current events, such familiar glamorizations offer spectacle born from violence. What is it that is gleaned from this entourage of data—does such information promote action, or act as a proponent of settler-colonial doomerism perpetuated by those committing the violence?

“History is littered with targeted–but no less deadly existential threats for specific populations,”12 as Black climate justice activist Mary Annaïse Heglar writes in her article uncovering the ways in which global peoples have survived through centuries of ongoing occupation and brutality. Related tensions appear acutely in so-called Vancouver as historical and ongoing Indigenous dispossession lends an uncomfortable seat for this same occupation to reside upon. Diverting life-bearing streams to the underbellies of highways as an expense of colonial experimentation, these spaces find themselves paved over to serve the minority few who benefit from slickened sidewalks. How can one listen to waters funnelled meters underfoot?

Daniel Wildcat (Yuchi, Muscogee) proposes an alternative view of place in his concept of the “nature/culture nexus”, being a “relationship that recognizes the fundamental connectedness… of human communities and societies to the natural environment and other-than-human” worlds.13 What's important is not knowing how to fix environmental concerns in review of cautiously made charts, but how to enter into relationship with place and their respective systems.

I guided participants to hear the water, but did we listen?

I sought to know how to better understand these bodies of water and their entwined histories through the extraction of data, to leave their shores in a manner as swift as my brief arrival. By means of colourfully rendered attempts at preserving collective nature-nostalgia against the onslaught of development, I guided participants to hear the water, but did we listen? Walking away from the sites of study with tokens, provided by the streams, we commodified nature’s loss and ultimately, made spectacle of its extraction.

What stories were the waters telling in those collectivized moments on their banks, if they were choosing to speak to the project at all? Through reflecting upon the impact and implications of The Freshwater Monitoring Art Kit, I called to question the epistemology of place and story, of altered ecosystems and whose science is seen to be valued over others. There has always been water within these sites, there have always been people within these landscapes to take notice. What does it mean to listen with intent through the lines of ecosystems to collectively remember and collaborate–how do we listen past the lines of extraction, present in the moment, acknowledging what is now and what may be to come?

~~~

I visit Still Creek, arriving at the lip of the ravine, bare of the data recording equipment that became so familiar to me the winter before. Over a year on from the last time I was a guest at the site, water trickles again, greeted by daylight as it funnelled through the culvert before me, a fate not afforded by the dozens of other waterways the bus had crossed on its way to drop me off.

The familiar chirps of American Robins and Jays reverberate through the divot of forest, I liken their calls to welcoming the stream back to atmosphere, cheering on its channeled marathon. Winter has passed through the land once more, frosting the tips of the moss-covered boulders that fasten the pathway to soil. My boots reach the lip of the creek and, sensing movement, I lock gazes with a fish. The fry darts into the casted shadows of foliage no sooner than I had noticed its company, the encounter startling both parties.

Having found home between the encasement of concrete and steel some 100 meters in every direction, I wonder what the remainder of her life will hold, destined inside this stream, down to the floodplains of the Fraser, or onwards to greater migrations and stories to share still. I remain standing for as long as morning weather will allow, noting a last detail before I depart. The ghosts of the past no longer reflect back upon the rippling surface.

From the artist

Joshua (they/he) is an uninvited settler-occupier on the shared and stolen lands of the Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. Born on Treaty 2 Territory, he is of mixed white ancestry of English, Scottish, and Métis. He can often be seen partaking in habitat restoration or looking at birds.

Learn more about the Invasive Art Initiative.

Make it personal

Is there a time you listened with intention recently?

Urban Stream Stewardship: From Bylaws to Partnership: An Assessment of Mechanisms for the Protection of Aquatic and Riparian Resources in the Lower Mainland: Summary Report. (1996). Dovetail Consulting, 1

Todd, Zoe. (2017). Fish, Kin and Hope: Tending to Water Violations in amiskwaciwâskahikan and Treaty Six Territory. Afterall a Journal of Art Context and Enquiry, 96.

Kulkarny, Akhsay. (2021). A Look Back at the B.C. 2021 Wildfire Season. CBC News.

Bell, Niko. (2021, August 4). Uncovering the History of Vancouver’s Hidden Waterways. Montecristo Magazine, Vol. 14.

Andreyev, Julie. (2021). Lessons From a Multispcies Studio: Uncovering Ecological Understanding and Biophillia Through Creative Reciprocity. University of Chicago Press, 135.

RivInstitute. (2012, November 9). Salmon return to Still Creek [video]. Youtube.

Home Property Development: Still Creek Enhancement. City of Vancouver website.

Solnit, Rebecca. (2005). A Feild Guide to Getting Lost. Penguin Books, 57.

Oliver, Mary. (2016). Upstream, essay except. Penguin Books.

Brevik, Kristian. (2024). Noticing is not Enough: A zine about birdwatching, hunting, and survial. Self-published.

Employing Max Liboiron’s [Michif-settler] argument against the term “western science”.

Heglar, Mary Annaïse. (2019) Climate Change Isn’t the First Existential Threat. Medium: Zora.

Wildcat, Daniel, R. (2009). Red Alert: Saving the Planet with Indigenous Knowledge. Birchbark Books, 50.